Not only have temperatures soared across the northern hemisphere in July and August, but so have prices. In fact, inflation has been rampaging pretty much everywhere this year, for reasons of war, drought, politics and pandemic1 Whether you are inclined to the apocalyptic view, or something more measured, these are certainly challenging times. And even when inflation peaks, price rises for most goods and services rarely retreat – at best, they plateau.

So as a business, your input costs (raw and manufactured materials, fixed and variable overheads, wages and external fees) have probably risen. And you don’t need a Nobel prize in economics to work out that either you follow the herd with a price increase, or your margins quickly fall. Would any businesses opt to hang on to their clients and customers at any price, for fear of losing them to a cheaper competitor, and wait for the storm to pass? Perhaps. But if not, at some point the vendor has to take a deep breath and ask for a price rise.

Let’s move away from the economics and consider the behavioural models that might just help. Our research into account strategy and negotiation over the years perhaps offers some pointers.

One option adopted by some suppliers of relatively scarce goods is simply to announce and then impose price increases, safe in the knowledge that the customers depend on them and will only face the same wall of large dollar signs if they seek alternative sources. That’s a strategy open only to a few – usually very large or very specialised – vendors. For the rest, there is at least some power in knowledge.

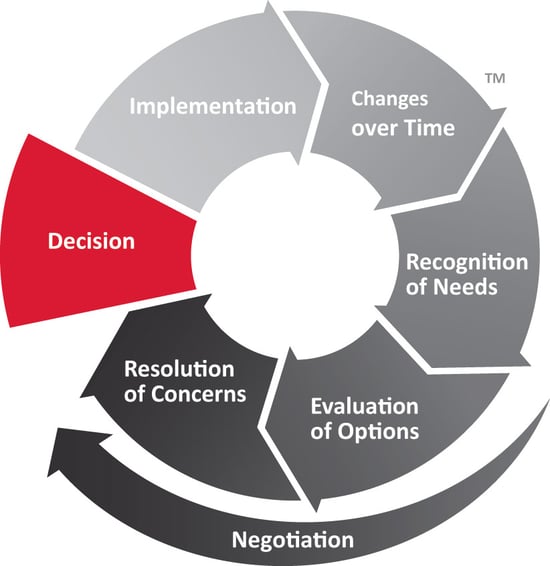

Research into what competitors are doing and – more importantly – some informal questioning as to what customers are themselves being subjected to from other suppliers can be useful in setting the scene for what will become – inevitably – some form of negotiation. It’s a conversation that only account managers who are actively curating their day-to-day relationships with customers during the Implementation and Changes Over Time phases of the Buying CycleTM can initiate without being chased away with boxed ears.

Goodwill hunting

You can’t build more value for the particular and maybe unique benefits that your products or services are delivering if you’re not in a continuous account management dialogue, and you can’t usually create that retrospectively.

The renowned expert in contract management Graeme Sloan2 once taught me, in this context, about the idea of a “goodwill register”. Basically it’s a list, containing as much detail as you can compile, of things you as a supplier do for the client that were never part of the original contract, but which mission-creep or just the fact that you’re a nice person have allowed to become the expected norm. A special one-off deal on disposable supplies; an extra day of user training that was never charged for; not imposing the late payment penalties that you’re actually entitled to in the master services agreement; letting the volume discount stand even though the ordering threshold was undershot by 10%. When those things are in the past they are harder to document than if you keep a contemporaneous record, but not impossible if you give it some serious thought. Either way they can be powerful.

Once you are sure of your ground on the goodwill you’ve expended, start asking questions – one by one – about the value that each of those individual, specified aspects of the relationship brings. We call this Seeking Information, and as we know from the research, questions create doubt and doubt creates movement. Lead the conversation to a place where the customer starts to realise for themselves not just the value that they currently get, but the obvious impact that providing that goodwill has on your margins in the current situation. Get them to consider whether they could get such added value from a cheaper alternative source – and what they would lose thereby.

A good, related question might be: “If we don’t raise our fees, which of the services we are currently providing do you feel you could most easily do without?”, provided you are confident they won’t identify something that costs you very little to provide. And to be clear: this is not to be used as moral leverage; this is actual, business-like leverage, based on the objective interests of each party.

Verbal behaviour is good behaviour

That done, you might need to coach your contact in the customer organisation to have that same conversation with their colleagues in procurement if procurement is – as they might well be in this discussion – the true Focus of Power. For a discussion of what I mean by that term, read our blog post.

Think about fallbacks. Going into a price discussion knowing that you have alternative customers at a price that would still be profitable (or less costly to service) is a fallback. If you know that the present customer has few other supply options and that changing would be disruptive and costly for them, their absence of such a fallback is a notable source of power in your head. Setting the right climate and focusing on common ground3 is important here so anything you say is taken in a spirit of finding a solution to a shared problem, not blackmail.

If you do get into a more animated discussion about your needs versus theirs, in what the present circumstances might be turning into more of a zero-sum game, avoid labelled disagreement (it’s better to lay out your argument while they are listening, and the research suggests that people switch off when you announce that you are about to disagree with them)4. Try also to avoid irritators (again, the research reveals that telling the other party that yours is “a very fair offer” is unlikely to be persuasive)5.

Instead, try and get the other side to articulate, in spite of the answers they have given to your own well-constructed questions, why they should be exempt from an increase, and why you should be unique among their suppliers in not getting one. And then use incredulous testing understanding6 to reinforce the logical poverty of such a position. In other words, quote what they’ve said back to them: “So, to be clear, you’re saying that you don’t think you should pay 2.4% more for a product all of whose components have risen by 11.3%, although the average price increase by your other suppliers of similar products this quarter has been 7.2%?”.

It’s especially helpful if you have done some research along the way into whether they’ve been busy raising their own prices to their customers for the last six months. That information, properly used in the verbal encounter, can be powerful in undermining any denial (as a client tried to suggest to me recently) that prices are rising generally. The people buying your service might not actually know that the people selling theirs are seeking to cover higher costs.

Nobody is pretending this is the most pleasant conversation you’ll ever have. But it can be had without rancorously undoing all the hard work you’ve both put into the relationship – if you focus less on simply preparing the stark economic case and more on planning the behavioural aspects of the conversation.

Notes

-

https://sums.org.uk/our-team/principal-consultants/graeme-sloan

-

At the negotiation planning stage, skilled practitioners mention Common Ground 3.5 times as often as the average practitioner.

-

Labelled Disagreements are 4 times more likely to be used by average negotiators than by skilled negotiators. By contrast, labelling other behaviours (such as asking questions or supporting) is associated with successful negotiators, who do it over 5 times more often.

-

Average negotiators use irritators like these 4.7 times more often than their skilled counterparts.

-

Testing Understanding generally is strongly associated with successful negotiators who do it over twice as much as average negotiators.