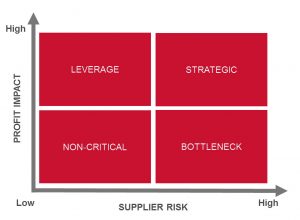

Peter Kraljic’s Product Purchasing Classification Matrix has been used by procurement professionals for more than three decades. It enables buyers to classify goods and services that the company purchases and devise strategies according to the classifications.

In the previous blog I looked at how behaviours that procurement professionals use in negotiating with non-critical suppliers are usually not appropriate when negotiating with strategic suppliers. How to negotiate more productive strategic deals is to establish common ground at the outset and to maintain and develop it through the course of the negotiation. Failure to do so will inevitably result in sub-optimal deals.

Supplier risk is about scarcity. How unique is the supplier’s solution? In other words, how many competitors does the supplier have? A supplier with few or no competitors will constitute high supplier risk.

The computer chip manufacturer that is making bespoke chips for a mobile phone company, jointly undertakes market research with the phone company and has some of its employees working on the phone company’s site would be very difficult to substitute and so constitutes a high supplier risk.

On the other hand, a supplier of office stationery to the mobile phone company will have many competitors and will be categorised by the phone company as low supplier risk.

Profit impact is about the financial impact of the good or service. How dependent is the company on the supplier for its financial success?

In the case of the computer chip manufacturer it is clear that its chips are at the heart of the mobile phone company’s product which means that it has high profit impact, whereas the supplier of office stationery has insignificant profit impact.

The Kraljic model enables buyers to categorise suppliers and devise strategies around these categories.

To return to the example of the mobile phone manufacturer, the computer chips clearly fall into the Strategic category and the strategy adopted by the phone manufacturer would probably include developing a long-term relationship with the supplier, closer cooperation, perhaps in the form of a joint venture or purchasing the supplier.

The office stationery falls into the Non-critical category so the phone company will try to optimise price, order volumes and inventory. It should be able to switch suppliers easily if a better deal were on offer. The phone company’s relationship with the stationery supplier will probably be transactional.

However the office stationery supplier may also supply paper to a printing company. In this case, the printer would probably regard the supplier as low risk but having high product impact and the stationery supplier’s paper would be categorised as a Leverage item. The printing company will try to leverage its purchasing power through high volume orders and by using substitute suppliers.

The computer chip manufacturer might also supply low tech chips to a company producing lighting systems. The profit impact is not high but the supplier risk is, so the lighting manufacturer would classify the chip supplier as Bottleneck. The problem for the lighting company is that, although the chips are of low profit impact it could be compromised by shortage of supply. Its strategy may then be to place large orders and stockpile chips to ensure consistent supply. In some cases buyers may encourage competition by assisting other companies to enter the market.

This time I would like to look at a group of behaviours that we at Huthwaite have termed ‘Low Reacting’.

Reacting behaviours are:

- Support (a behaviour that makes a conscious and direct declaration of agreement or support for another person or for the ideas and opinions of that person)

- Disagreeing (a behaviour that states a direct disagreement or which raises objections or obstacles to another person’s ideas or opinions)

- Defend/Attack (a behaviour that attacks another person either directly, or by defensiveness and usually involves value judgements and contains emotional overtones)

Low Reactors use little or none of these behaviours. And our research has demonstrated that sellers are usually rattled when facing a Low Reactor.

Sellers are normally enthusiastic about their product or service and would like the buyer to share that enthusiasm. Getting no reaction from the buyer is disconcerting. Sellers often dry up, lose sequence and even exaggerate claims about their offerings. But, more importantly, sellers have a tendency to make concessions when faced with a Low Reactor.

Most procurement professionals low react, often unconsciously, not because they have been trained that way, but because they have learned that behaving that way frequently helps wring concessions from the seller. While some may decry the use of low reacting it is nonetheless widely used because it is effective.

However, problems arise when low reacting is used in strategic negotiations. The effect is to make the negotiation more positional, reduce the level of trust and inhibit the flow of information, thereby losing opportunities for creative long-term solutions.

Again this demonstrates the need for behavioural flexibility: the ability to recognise that different circumstances require different strategies and different behavioural sets to support those strategies.

Huthwaite VBA Complex Negotiation courses include Behaviour Analysis of each participant with feedback and the opportunity to compare own data to research-based models. Participants can then assess their own reacting levels and make any adjustments to suit the various negotiating situations that they find themselves in.

.jpg?width=675&name=iStock-623524380%20(1).jpg)