A really first-class blog recently appeared on the McKinsey & Co website and, as you’d expect, it’s a mix of common sense, illustrative anecdote and – though it’s not made explicit in the piece – presumably some hard evidence.

In it, the authors (Field, Hancock and Schaninger since you ask) argue that, “…we need to view middle managers as being at the centre of the action. Without their ability to connect and integrate people and tasks, an organization can cease to function effectively. That’s why we think the best middle managers are best off staying exactly where they are…”.

And – in my long experience as a middle and senior manager, steely-eyed observer of large and complex organisations, and consultant – this is true. The gist of their article is that middle managers fulfil roles and tasks that are particular, valuable and discrete from other positions up and down the corporate greasy pole. The pity of it is that everyone (including the occupiers of those intermediate job functions themselves) seems to assume they should be on a path to bigger and better things. And the question is: shouldn’t everyone value those roles and those people as highly as any top executive or respected expert? The truth is, many organisations could not function without them, even in the down-sized, rationalised, streamlined, AI-ridden world of 2023.

So, if we accept that premise, what skills (other than the specialised functional skills for which they are specifically employed) does this group need in order to, in McKinsey’s words, “connect and integrate people and tasks”?

The much vaunted and widely peddled notion of “emotional intelligence” might be helpful in catching, in passing, the superficial attention of anyone looking to answer this question. But for something of practical use, it’s far more helpful to think in terms of identifiable and separately observable verbal behaviours.

First, there are meetings. (Aren’t there always?). But it’s an unavoidable truism of corporate life that – if people are to have ownership and commitment to ways of doing things, and if knotty problems are to be unknotted – there will always be meetings – short or long; formal or informal; large or one-to-one; reluctantly or happily convened. Whatever they look like, they play a vital part in the success or failure of anything a company is seeking to achieve, and typically the middle manager is at the heart of them: sometimes chairing them and trying to get a recommendation to take up the line for sign off; sometimes playing a contributing role, chipping in to help generate ideas for the group while being watchful to protect the interests – and promote the value – of their own immediate team.

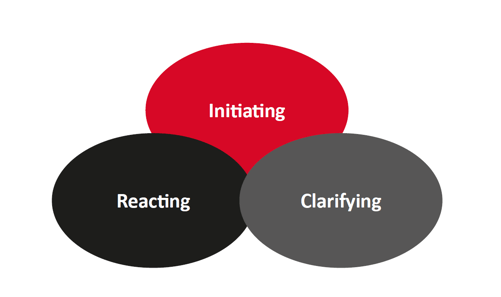

Understanding that there are three main areas of behaviour in any meaningful verbal interaction is a prerequisite. Any middle manager in the presiding chair, or in any of the contributing seats representing their team to the senior suite and vice versa, needs to command these skills as second nature.

In that context, they first need to know the difference between what we call a Filter Meeting and an Amplifier Meeting, and possess the verbal skills to either drive, or support, either one effectively. Filter, for when the group needs to reduce several possible choices of action against time constraints, and where not everyone around the table actually has to buy-in to the decision for it still to be implemented successfully. Amplifier, for when the organisation needs to generate new, high-quality solutions where no pre-existing alternatives are available and where everybody needs to be fully committed to the outcome if it is to work. And, whilst on that subject, drawing up a meaningful agenda for such a meeting automatically eliminates those annoying encounters that could just as easily have been avoided by a thoughtful exchange of emails, WhatsApps or Teams discussions.

Understanding and inhabiting those behaviours and realising what their correct use can achieve – for a career and an organisation alike – ought to be high on the middle manager development competence plan.

Secondly, persuasion. It isn’t enough merely to influence, to be recognised and respected as a person of sound judgement and integrity. That status might mean that people are happy to consult you. Your sage pronouncements might get a sympathetic hearing, possibly leading to the right course of action. But persuasion is something more. It requires behavioural skills which are surprisingly uncommon and are rarely either naturally occurring or efficiently trained. And that’s because most people’s natural setting when persuading is Push style, rather than Pull. And, as nearly 50 years of Huthwaite research shows, Push is often over-used to an extent that is counter-productive. Each style has its uses in different circumstances. For example:

-

Consider who has the power in the particular situation: you, or the person you are persuading? (Note: power can derive from position, expertise, personality or resources). If you have power, push works best; if not, pull will be necessary.

-

Does it matter if you are seen to fail in this particular instance? If so, Push would be high-risk – you’ll reveal your desired outcome but it will be more visible if you then don’t obtain it. If not, using Pull can conceal your desired outcome, lowering the stakes considerably.

-

Do you need to gain the commitment of the other party in order for your idea to be implemented successfully? Using a Push style here will probably obtain low commitment through low involvement, whereas a Pull style will produce a decision to which all stakeholders feel committed and a sense of ownership.

-

Does it matter if the other party comes away feeling that they've lost the argument? Bear in mind here that the knock-on effect of that could be that they will be more guarded or aggressive next time around. Push is more likely to result in Win-Lose, which might be fine for the future relationship, but you need to be sure. Whereas Win-Win might be harder work but can often result in a more robust long-term outcome.

-

Do you have a lot of time to plan and execute the persuasion? Push, obviously, requires less time to plan and might be appropriate where an immediate decision and action is critically important: fire-fighting can’t wait, which is why the places fire brigades make those decisions are known as command-and-control centres. Pull requires time to plan, and takes longer to execute, but might enable the group of which the middle manager is at the centre to arrive at solutions with greater nuance and sophistication.

It might even be that the right application of these behaviours by middle managers will help to create an environment of “psychological safety”, a phrase that has followed “emotional intelligence” into the management-speak lexicon without so much as a backward glance to see if it has any true meaning. But if it means influencing and persuading people to do things in an atmosphere from which coercion and conflict are absent, and where co-operation and reasoned adherence abound, then Push-Pull proficiency might be said to be a middle-manager’s behavioural tool for psychological safety.

Our research indicated three key features of how effective persuaders use Push–Pull:

-

they are adept at using both Push and Pull styles of persuasion

-

they will choose which style to use depending on the specific nature of each persuasion

-

once they have chosen which style to use, they will stick to it – they won’t switch or mix styles within the same persuasive interaction.

Finally, we can’t avoid modern reality that some of the naturally occurring incidences of these behavioural skills sets were lost during lockdown. Or to be more accurate, they were replaced by new behaviours and protocols specifically appropriate to the virtual world. Now is the time to get some of those back into daily use. What might some golden rules be in that case?

Don’t let the fact that you can now see people in three dimensions and at a size bigger than a window in the corner of the screen fool you into over-valuing the importance of body language. It’s actual language – verbal behaviour – whose successful deployment is the determinant of communication success. Be conscious of airtime. There might be times when you need to take more of it, but invariably, seeking information rather than giving it is correlated to success in commercial and non-commercial persuasion settings. Don’t be afraid of silence or other people’s questions. Often, other people are low reacting or asking you questions to give themselves thinking time and to create doubt (and thus movement) in your own mind. Don’t fill the void with something you’ll regret just to avoid awkwardness. Every word carries weight.

Middle managers are just one of the groups of managers and leaders that Huthwaite’s Leading Behaviours suite of skills are designed to help. But experience suggests that they are the people most often on the front line in any conflict. So, organisations would do well to equip them well with the armour of behavioural skills to listen, to help conflicting parties out of defend/attack spirals and to find the best ways forward.

We’ll return to others in future blogs. But as those clever folk at McKinsey have said: “the people who excel at middle-management jobs are true superstars”, and surely it’s worth the effort to give the them help they need to shine.

Learn more about Huthwaite's leading behaviours. Book a consultation now.

.webp)