Already bored of people talking about how things will never be the same again? Finding the phrase 'the new normal' tedious yet? Worried by the blithe assumption that we are now entering the 'post-Covid' phase, when globally it is in fact still accelerating?

So why don’t we steer clear of the megatrend analysis and look instead at some of the practical ways in which certain business practices are necessarily different at the moment, and won’t quickly change back?

In my last two articles In these unprecedented times, what are customers thinking? and Will virtual selling be normalised sooner than we thought. I examined current alterations to look for in buyer behaviour. If people are currently buying and selling in the virtual world where technology is replacing the face-to-face meeting, then it stands to reason that they are negotiating that way too.

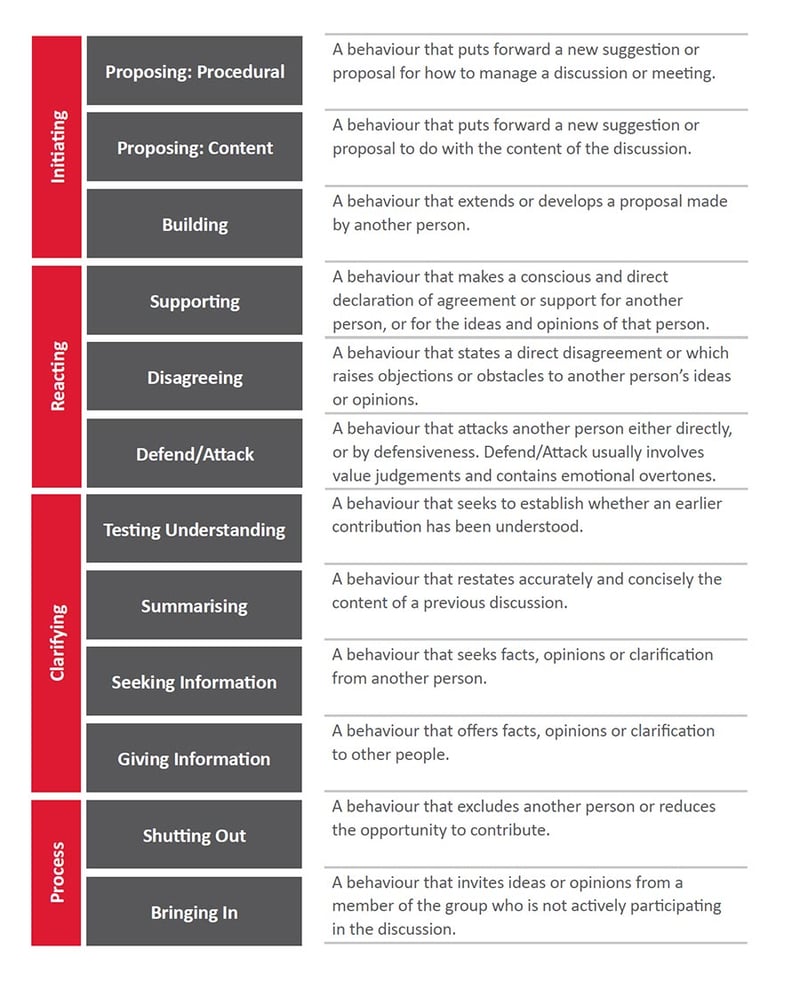

As we know from close on 50 years’ research into the subject, probably the biggest determinants of success in any negotiation are the skilled deployment of, and subtle responses to, certain categories of identifiable verbal behaviour. Broadly, there are 12 categories, falling into four groups.

Of those behaviours, eight, according to the observational data, are most closely correlated to successful outcomes in traditional real-word negotiations. The four that are most sparingly used by top negotiators (Disagreeing, Defend/Attack, Giving Information and Shutting Out) should still be treated with the utmost caution in the virtual world. Of the remainder, Procedural Proposing, Supporting, Testing Understanding, Summarising and Bringing In have had their importance magnified lately. Since we started seeing our negotiation counterparties as pixelated personalities with unfeasibly long hair and in the midst of child- and pet-care duties, have we started behaving differently? In one sense, we have – because technology has made it so. And this, I would argue, both changes and reinforces the role of verbal behaviour.

Some negotiation has always happened as a verbal-only, non-visual process. After all, there have always been times when we’ve sewn up deals, traded price for volume or agreed a contract revision in the course of a voice-only phone/conference call. We’ve used email too, and perhaps now even shorter forms of written platform.

Equally, the visual conference media we’ve grown so used to in the past four months are not exactly new: I conducted negotiations over Skype for years before the present crisis.

For the most part, until February 2020, the general assumption was that at some point in a major, complex, high value negotiation, people would meet. And in doing so, the verbal behaviour they displayed and encountered would be rounded-out with all kinds of other non-verbal cues and clues that helped people to understand where they were in the process.

A quick word on those clues we do have. When the camera is on, one of the most pervasive and obtrusive sources of facial expression is ourselves. We are always there in the corner of our own screen, and as we try to concentrate on a detailed argument about IP rights protection in exchange for 12 months’ exclusivity of supply, we might also be noticing that we really do need a haircut and a visit to the dentist, and wondering if the ostentatious display of texts on the shelves behind us might be sending the wrong message to our particular audience. Those thoughts creep in and distract us from the delicate matters in hand. We can also become so conscious of the messages we believe our facial expressions are sending, that we artificially alter them (though as we should know, most of the received wisdom about detailed interpretation of facial expression is, in fact, mostly hocus pocus).

So it might be a good idea to turn off our camera, or to use a setting where the other party can see us and we can see them, but we can’t see ourselves.

But in a virtual conference – especially if you are leading it – there are still extra challenges. Often, major negotiations involve a mix of specialists on both sides. There might be lawyers, HR managers, financial people, technical buyers, salespeople, procurement category managers and many others involved. They might all be participating in a plenary discussion, in which case does your virtual platform have enough frames to keep them all in view? Or they might want to have parallel stream discussions about different aspects of the agreement, in which case does your chosen virtual platform have enough break-out rooms to accommodate them all and do you know how to manage them? Do you then know how to bring them all together and how do you keep track of what has gone on in each of them?

If you are hosting the negotiation, always have at least one person on the conference from your side who is an expert in managing virtual rooms and has no other role in the negotiation than to do that. As well as technical skill, you will rely very heavily on two crucial behaviours: testing understanding and summarising. These are important when the negotiation is face-to-face. When it is virtual they can be the difference between success born of clarity, or failure born of anarchy.

Because it might be difficult to attract sufficient air time in a multi-party virtual negotiation, where your face isn’t visible to everyone and people are all leaping into fill apparent breaks in discussion occasioned by broadband lag, there’s a terrible temptation to rush things when your time does come. At this point, confusion about what you are saying, due to failure to label the behaviour you are about to use, is a grave risk. Skilled negotiators label the behaviour they are about to deploy (proposing, seeking information, supporting, giving feelings etc, (but not if it’s disagreeing) almost five times more than the average negotiator. When it’s a Zoom not a room, you might forget to do this in your anxiety to be heard, and everyone else might be left to interpret why you have grabbed the microphone and what, exactly, you are trying to communicate. Worse, you might rush in to respond to a proposal with an immediate and unconsidered counterproposal – something less skilled negotiators do twice as much as skilled.

Instead, use that precious airtime, first to check that it’s appropriate and timely to make an intervention (so avoiding another negotiation deadly sin: shutting out), and then to seek the information that will allow you to complete your picture and build your case.

And that feeling of rush and hurry can have a negative impact on bargaining. Our research shows that it’s best if you can leave space for the other party to make the first move; that if you make an offer, you should seek a reaction to it; and that you should keep all issues available to trade until the deal is ready to conclude. Each of those tactics requires time. So too does dealing with Low Reactors – people for whom less than 10% of the behaviours used fall into this Reacting category, and who might even use the excuse of “sound quality issues” to exacerbate the tendency. Ask questions about their feelings; require that they do react before you move on; and express your own feelings (eg of disappointment at their low reaction to important questions). Virtual meetings with many people and multiple “hard stops” might militate against the available time to achieve all of this. So don’t be afraid to summarise what has been achieved and suggest (labelling vigorously as you do so) that it all builds into a viable agenda for another session (perhaps not requiring every single party).

The peculiar background to everything we’re having to do differently this year could, if we’re not careful, add to the normal verbal irritators that adherents of Huthwaite negotiation skills will be familiar with. For example, in addition to notoriously dangerous self-praise phrases like “it’s a very fair offer” or “I’ll be honest with you”, there are some new ones. One would be constant reference to “in the current crisis” and “bearing in mind the unprecedented times we are living through”. Nobody on the call is unaware of the present circumstances, everyone will have heard them before and many people will interpret them as a substitute for rigorous thought. A lazy negotiator may use Covid-19 as cover to justify price positions or proposed contract terms when – in fact – it might have no bearing one way or another. A skilled negotiator on the other side will spot this, and it then morphs into another trap for the unwary: argument dilution. Our research shows that skilled negotiators use fewer than two thirds as many reasons to back up their arguments than the unskilled. The best negotiators identify where their case is strongest and concentrate on solidifying those positions with evidence; they don’t present a soft underbelly of ill-considered reasons that skilled opponents can undermine one-by-one. The virus might just be one of those.

As well as being watchful of our verbal behaviour, we should also be grateful for some of the undoubted advantages conferred by our new tethering to negotiation via laptop.

For one thing, if we do need to set up extra sessions or break outs (even brief ones) to thrash out the minutiae, it’s simpler and cheaper to do it virtually than in an era of mass travel and accommodation. And we’ll probably get better, more enforceable agreements as a result. For another, if all parties are agreeable, the use of annotation and chat tools, and even the little red recording button, are good ways to banish post factum arguments about exactly what was said and agreed.

And finally, all the tools of the negotiator’s trade – in Huthwaite terms they would be the Negotiation Organiser, STREAK Analysis and Trading Tool, as well as spreadsheets, draft contracts and standard T&Cs – can be spread out on your desk (or kitchen table) for you to consult and annotate. That’s a liberty you could never take in a conference room at your customer’s HQ or the business suite of a Holiday Inn. The things you want to see but you don’t want the other party to see are all there for you to use as you wish – if you can keep the ketchup and the kids’ homework a safe distance away.

.webp)